So from here on out is my post...

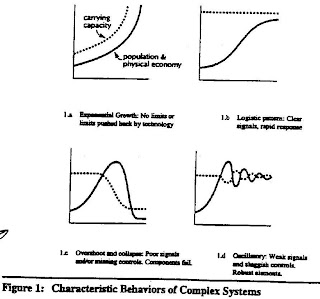

I want to focus on the two components of the article that really impacted me. The first was the 4 graphs he used to illustrate fundamental behaviors of complex systems. I thought this was absolutely fascinating. I respond well to formulas and graphs, because they methodically illustrate a point that can otherwise be difficult to explain. Ehrenfeld uses those 4 graphs to explain how fundamental characteristics of a system can drive the exact same starting conditions into 4 wildly different results. And when you use those graphs to model our macroeconomic system, it becomes clear how critical it is that our economy be properly constrained to avoid a catastrophic crash (akin to his point on extinction).

He talked about how the system has to have signals that can be recognized quickly enough by a control system that can react quickly enough. If the signals are too slow or are unclear, or the control system is too slow to react, then the system will crash out. And this is exactly what we at Presidio fear is happening. We can see that signals aren't clear enough to drive unanimous action by society. And even if they were, our control systems (governments, corporate boards, NGOs) are too slow, too divided, or too powerless to react quickly. And on top of that, there are enough people who believe our macroeconomic model fundamentally looks more like any of the other 3. So most of us here at Presidio might look at all of this and think, oh great, we're screwed. And screwed we may be, but hey, at least we've got a great way to represent it all graphically.

The other neat part of the article was Ehrenfeld's discussion of what he saw as a radical paradigm shift, which he eventually suggests is embodied by industrial ecology. It's not the idea itself that industrial ecology is the new paradigm that I found intriguing. No, instead I was drawn in by this discussion of the very definition of sustainability. He makes it clear that sustainability isn't a technological or economic state of being, but actually a moral choice made by the agglomeration of moral actors in society (e.g. all of us). Some people may react with a "well, duh." But I'm not latching onto the superficial definition of morality here. He's talking about something far deeper than making a moral choice to not drive a car, or to eat vegan, or to never brush your teeth again so as to avoid wasting plastics and toothpaste.

No, he's stating that we are making a moral choice about the kind of world we want to persist indefinitely. Ultimately, as the only self-aware beings on the planet with the ability to effect massive global change, we can choose the state in which we want the world to exist, and then we can freeze it there indefinitely. When we talk about sustainability today, we talk about preserving the world as it stands, with its polar bears and spotted owls and temperate Europe and unflooded coastal zones. But that's a moral choice. We've already vastly impacted this planet; why would we choose to freeze it as it is now? Why not try to rewind to a pre-industrial America and freeze that? Or fast-forward to a Europe covered in glaciers and freeze that? Or ride it out for 500 more years and then freeze whatever post-apocalyptic wasteland exists at that point?

The point is that we're making a moral choice to freeze things where they are today. Is it the right choice? To us it seems like it is. But Native Americans, buffalo, and North American elms and chestnuts might disagree. They'd likely all prefer a world frozen at year 1400 development. And people who own property at 50 ft above sea level might really prefer we wait until the ice caps melt before we freeze things. And on top of all that, there are people who won't want to freeze at all, because it's too hard, or because they just don't care if the world as it exists persists indefinitely, because they place no moral value on future generations, or assume that those future people will adapt and live just fine with whatever they've got (just as we have!!).

So all of us trying to push for a freeze should be aware of exactly what it is we're doing: we're making a very selfish moral choice. Our decision to sustain our current world is not an absolute in the realm of morality. It is highly relative. It's relative to our personal preferences, our personal histories, our personal biases. We don't want to roll back North America to the year 1400 because we live here and don't want to leave. But we do want to freeze the world as it is now because we like Florida and our coastal cities, and we like polar bears and spotted owls and forests and a de-iced Europe. But the cold hard truth is that there's nothing inherently more valuable about any of the things we like than there is about the unspoiled Great Plains or the un-touched Great Northeastern Forest.

So think about that. Get comfortable with your selfishness. And then go out and save the world that you know and love, and say goodbye and that you're terribly sorry to all of the infinite other possible worlds whose existence you're denying. For all you know, they're better than the one you're choosing. ;)

2 comments:

A friend of mine encouraged me to check out your most recent post.

I would say I was unaware of this concept of "freezing" that you and your colleagues had, and would proceed to declare that the notion of "freezing" our ecosystem, our society, etc. is unrealistic and ignores the nature of . . . well, nature.

It is actually something I have railed against with cultural preservationists, frequently outsiders who have tried to encourage my minority community to keep intact their language and "culture." They seem to fail to recognize that it is not an outsider's responsibility to try to impose/guide/direct the development of a culture and that the direction of any ethnicity/culture lies within its constituents. Furthermore, it fails to acknowledge that the present-day Latino culture (to which I am personally referring) is the product of centuries of evolution, change, destruction. To try to stand as an outsider and decide the future direction implies a sense of superiority that is ridiculous and offensive, in so doing one inherently sets oneself up as a a judge and as a pseudo-deity.

It may have seem that I have made a serious digression here (and in many ways I have), nonetheless, I believe these points translate to the topic at hand.

We have such arrogance as human beings, propogated by Judeo-Christian misconceptions of Adam and Eve that this earth is here for our use and exploitation. That we set ourselves up as psuedo-gods to decide what must die away and what should be preserved. Where in our limited wisdom do we suppose such omniscient omnipotence?

We are members of this world ecosystem. We must accept that it changes and must adapt to its changes. To acknowledge the ebb and flow of the universe is to respect it and, no longer as an enemy to it, be in harmony with it .

I would advocate, rather than trying to "freeze" the system (which to me at present seems rather diseased), to genuinely take accountability for our place in the ecosystem and strive to dramatically reduce our footprint, more correspondent to our place as members, rather than rulers, in this ecosystem.

Our intelligence does give greater responsibility, but as any parent can tell you, responsibility usually means greater sacrifice.

Your post was about morality, and in your post you are correct in stating that present-day institutions are too slow to respond to the dilemmas we face. However, we live in a system that is ruled by the will of the people (this is the nature of capitalism and (to a lesser degree) democracy (ha ha)). A change in morality begins in each and every home, and encouraging a greater sense of personal accountability, compassion, and extended vision. If we foster these in our homes and amongst our children, not only would we be less inclined to toxicity towards the environment, but also towards each other.

I do not say this as some pipe dream, utopian vision, I genuinely think that pushing towards these attitudes in home, school, community programs would create an economic change that would have a real impact on environmental policy and practices.

Whew! Well okay that was a long response. Sorry about that.

Ok, I'm going to try again - I wrote a really long comment earlier today, but the internet seems to have eaten it.

I have a couple of issues with your moral relativism argument. Mainly, that we are not choosing to freeze our ecosystems at some point in the past not because we are selfish, but because it's simply not possible. No matter how hard you try, you can't bring back extinct species and vanished ecosystems. Even if you were to try to bring back, say, the northeastern forest, and cleared everyone out of New England (and beyond), it wouldn't come back the same - there would be huge areas that wouldn't convert easily to forest, either because they're paved/built up, or because they're polluted beyond the ability to support such large growth. And then there's the whole many extinct species problem.

So our choices become to act or not to act. I think it's pretty clear that if we continue on our current trajectory, things are going to get a lot worse, quickly, and not just for our species, but for a lot of others (hello, gulf of mexico dead zones!). I'm not convinced that acting is a relatively more selfish behavior than waiting to act,in this case. Because our reasons for waiting to act are (as a western society) not wanting to give us this unprecedented level of luxury that we enjoy. Acting to reduce our negative impact requires, on an individual and social level, some fairly un-selfish behavior. Giving up SUV's, acknowledging that the economy can't continue to grow unchecked forever, upgrading our personal technology less frequently, completely reformatting our energy supply system. Fundamentally, of course, by doing these things, we ensure the continuation of our habitat and the survival of our species, so yeah, I guess tat's "selfish" but on a short-term basis (within a lifetime or two) it reads as deprivation (not that it actually is deprivation. just feels like that to those of us in the first world)

So we as a society are faced with choices - wait to act on climate change/peak oil/pick your upcoming tragedy, or act now to reduce our negative impact. When the reason for waiting is mainly "I want to play with my toys a little longer," acting now becomes the responsible, not selfish choice.

As for freezing things at their current state. I assume you meant freezing our current ecological state. Frankly, we need to do a lot more than stopping the damage. We need to work hard to mitigate a lot of the damage that has been done already (pacific garbage float, superfund sites, monoculture farming practices, etc). At any rate, there will be exctinction, evolution, and general shifts in the environment even if (when?) we start to seriously reduce our negative impact, so it's never possible to freeze things at a particular point in time.

To do that, we're going to have to fundamentally change our social fabric. Not an easy task. I just don't think we can fix the problem with our current mindset - that constant push for more, more, more.

I think all this rambling is to say that the moral relativism argument seems to be artificially constructed to the point at which it's useless. Too many of the "choices" given are either impossible or very unlikely.

BTW, check out goods4girls.org

I know that nothing is less relavent to your daily life, but I still think it's an awesome project and I'm going to get busy sewing when I get a chance(you know, with all my free time). Pass it along to all your girlfriends!

Post a Comment